The Indispensable Framework: An Analysis of GDPR's Necessity and Impact Across Finance, Hospitality, and Emerging Technologies

July 20, 2025 - SelfcomplaiAbstract

The General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR), enacted by the European Union (EU) in 2018, represents a huge shift in global data privacy governance. We examine the necessity of GDPR, tracing its origins from historical privacy concepts to the limitations of its predecessor, the 1995 Data Protection Directive. It shows the EU's strategic vision for imposing this regulation, emphasizing harmonization, the upholding of fundamental rights, and the integrity of the digital single market. We further dissect GDPR's foundational pillars, its seven core principles and enhanced data subject rights. We will explore its enforcement mechanisms, including substantial fines and their allocative implications. Furthermore, it analyzes GDPR's profound influence as a global standard, marked by its extraterritorial reach and its role in shaping international data protection frameworks. A detailed sectoral deep dive reveals the specific necessity and transformative impact of GDPR on the Finance, Hospitality, and Emerging Technologies. Ultimately, the analysis concludes that GDPR is not merely a regulatory burden but an indispensable framework for fostering trust, ensuring responsible innovation, and safeguarding individual autonomy in an increasingly data-driven world.

Introduction

The digital age has brought in an unprecedented era of data proliferation, where personal information is collected, processed, and shared at an exponential rate across myriad platforms and services. This rapid technological advancement has simultaneously amplified concerns regarding individual privacy and the potential for misuse of personal data (University of Michigan, n.d.). In response to this evolving landscape, the European Union introduced the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR), which came into force on May 25, 2018 (Kavya, 2025). This landmark regulation was conceived to protect the personal data and privacy of EU residents, establishing a comprehensive and unified legal framework that extends its reach far beyond the Union's geographical borders (Wenham, 2024).

This report asserts that GDPR is not merely a regulatory burden but an indispensable framework for upholding fundamental rights, fostering trust, and ensuring responsible innovation in the digital economy. It represents a critical evolution in data governance, addressing past shortcomings and proactively shaping the future of data handling across industries worldwide.

1. The Imperative for GDPR: A Historical and Regulatory Context

1.1. Tracing the Roots of Privacy: From Fundamental Rights to Digital Challenges

The concept of privacy, while seemingly modern in its digital context, possesses deep historical and philosophical roots. In the United States, the U.S. Constitution, though not explicitly guaranteeing privacy, has been interpreted by the Supreme Court to provide for a right to privacy within its First, Third, Fourth, and Fifth Amendments (University of Michigan, n.d.). A pivotal moment in American legal history was the 1890 Harvard Law Review article "The Right to Privacy" by Justice Louis Brandeis and Samuel Warren, which famously argued for "the right to be let alone" and raised early alarms about "instantaneous photographs and newspaper enterprise" invading private life (University of Michigan, n.d.).

Internationally, the recognition of privacy as a fundamental human right gained even more description with Article 12 of the U.N. Declaration of Human Rights in 1948, which unequivocally states, "No one shall be subjected to arbitrary interference with his privacy, family, home or correspondence, nor to attacks upon his honour and reputation. Everyone has the right to the protection of the law against such interference or attacks" (University of Michigan, n.d.).

Europe, in particular, has a long-standing tradition of explicitly recognizing privacy as a human right, extending its protections beyond the confines of the home to encompass family life, communications, and reputation (Hoofnagle, et al., 2019). This commitment was further solidified in 2000 with the European Charter of Fundamental Rights, which established explicit fundamental privacy rights in two distinct forms: the right to data protection and the respect of an individual's private and family life, home, and communications (Schroeder & Bravo, 2025).

A notable divergence in privacy approaches between the U.S. and Europe emerged in the 1970s. While the U.S. articulated Fair Information Practices (FIPs), the foundational building blocks of information privacy laws, it applied them seriously primarily to government entities (e.g., Privacy Act of 1974) and specific private sectors like credit reporting (Hoofnagle, et al., 2019). Europe, conversely, embraced and expanded these FIPs, applying them broadly across both public and private sectors. This distinction led to Europe viewing information privacy as "data protection," increasingly seen as a distinct legal concept from the general right to privacy, with a specific focus on ensuring the fair and due process use of data (Hoofnagle, et al., 2019). The evolution from an abstract "right to be let alone" to explicit "data protection" reflects an adaptation to the increasing complexity and pervasiveness of data processing in daily life. Early legal and philosophical discussions around privacy primarily focused on preventing unwanted intrusion. However, as technologies like photography and, more significantly, digital data processing emerged, the nature of privacy threats shifted from physical intrusion to the widespread collection, use, and dissemination of personal information. Europe's proactive stance, culminating in the explicit recognition of "data protection" as a fundamental right, demonstrates a legal and societal understanding that in the digital age, privacy demands active management and control over one's data, moving beyond passive protection to active data governance. This underscores how the rise of the "information age" directly necessitated a shift from general privacy concepts to specific "data protection" frameworks, particularly within the European legal landscape.

1.2 The Limitations of the Data Protection Directive 95/46/EC: Why a New Framework Was Essential

Prior to GDPR, the European Union's primary legal instrument for regulating personal data processing and its free movement was the Data Protection Directive (Directive 95/46/EC), enacted in October 1995 (Court of Justice of the European Union, 2024). This Directive laid down basic data protection elements, including principles such as notice to data subjects, purpose limitation, consent for disclosure, data security, and the right to access and correct one's data (Schroeder & Bravo, 2025). Its scope was intentionally broad, defining personal data as "any information relating to an identified or identifiable natural person" and applying when a data controller was established within the EU or used equipment situated within the EU to process data (European Parliament and the Council of the European Union, 1995).

Despite its initial intent, significant problems and limitations emerged with the Directive. As a directive, it mandated that each EU member state transpose its principles into national law. This approach, however, resulted in varied interpretations and inconsistent enforcement across the Union, creating a "patchwork" of differing national rules rather than a unified standard (Hoofnagle, et al., 2019). This fragmentation hindered the internal market, as businesses operating across borders faced a complex and inconsistent regulatory landscape (Hoofnagle, et al., 2019).

Furthermore, the Directive's territorial scope was limited, applying primarily to companies operating within the EU. This left businesses located outside the EU largely unregulated, even if they processed the personal data of EU citizens (Dessaints, n.d.). The Directive also focused predominantly on Data Controllers, with Data Processors having comparatively limited obligations (Klekovic, n.d.). The allowance for passive, "opt-out" consent was also deemed insufficient in an increasingly complex digital environment where individuals needed more explicit control over their data (Klekovic, n.d.). A significant deficiency was the absence of a mandatory requirement for data breach notifications (Klekovic, n.d.). The inadequacy of the legal framework was further underscored in 2014 when the Court of Justice of the European Union annulled a related directive (Directive 2006/24/EC), citing serious infringements of the rights to respect for private life and the protection of personal data (Court of Justice of the European Union, 2024).

The rapid advancement of digital technology, particularly the internet, exposed the inherent limitations of a directive-based, fragmented approach to data protection, making a unified, robust regulation like GDPR essential. The 1995 Data Protection Directive, a product of its time, was conceived before the widespread adoption of the internet. Its design as a directive, requiring national implementation, led to significant variations and inconsistencies across the EU. This fragmentation created legal uncertainty for businesses operating across borders and resulted in an uneven level of data protection for citizens. As online services became global, this "patchwork" of laws became increasingly inadequate, as companies outside the EU could process EU data without direct accountability. This technological shift thus directly rendered the existing legal framework obsolete, necessitating a more harmonized and comprehensive approach.

The shortcomings of the Directive demonstrated that a "rules-based" approach without strong enforcement mechanisms and extraterritorial reach was insufficient to govern data in a globalized, digital economy. The problem was not merely the existence of rules, but their practical effectiveness. The minimal financial consequences for non-compliance under the Directive meant that large companies often viewed fines as a cost of doing business rather than a prohibitive deterrent (Hoofnagle, et al., 2019). The absence of explicit extraterritoriality allowed global players to bypass EU standards by operating from outside its borders (Kavya, 2025). This experience highlighted that for data protection to be genuinely effective in a global digital economy, it required not only clear rules but also substantial deterrents and a scope that transcended national boundaries, directly influencing the design choices embedded within GDPR.

1.3 The European Union's Vision: Harmonization, Fundamental Rights, and Digital Single Market Integrity

The European Union's adoption of the General Data Protection Regulation in 2016, which became applicable on May 25, 2018, was driven by a clear strategic vision (Hoofnagle, et al., 2019). The primary objective was to protect the fundamental rights and freedoms of data subjects and to standardize requirements for data processing activities across the Union (Yale University, n.d.).

A key driver behind GDPR was the urgent need to harmonize data privacy laws across Europe. By establishing a "single, uniform data standard" for businesses operating within the 28 member states, the EU directly addressed the fragmentation and inconsistencies that plagued the previous Directive, which had hindered the internal market (Hoofnagle, et al., 2019). This shift from a Directive to a Regulation directly addressed the harmonization failure of its predecessor, creating a unified legal landscape essential for a true digital single market. The Data Protection Directive's reliance on national transposition led to "varied enforcement and interpretation," which explicitly threatened to "hinder the internal market in the EU." By enacting GDPR as a regulation, the EU ensured its direct applicability across all member states, eliminating inconsistencies and establishing a truly uniform standard. This direct legal effect was a deliberate and necessary mechanism to overcome the fragmentation that characterized the previous framework, thereby fostering a more cohesive and predictable environment for digital commerce and data flow within the Union.

GDPR is fundamentally a "rights-based instrument grounded in the recognition of personal data protection as a fundamental right" (Schroeder & Bravo, 2025). It builds upon the explicit rights established in the European Charter of Fundamental Rights, reinforcing the EU's long-standing commitment to privacy as a core human right (Hoofnagle, et al., 2019). The regulation was designed to be one of the world's "strictest consumer privacy and data security laws", aiming to bring personal data into a detailed regulatory regime that would influence data usage worldwide (Bloomberg Law, n.d.); (Hoofnagle, et al., 2019).

To ensure effective compliance and deter violations, GDPR introduced significantly higher sanctions than its predecessor. For severe violations, as outlined in Article 83(5) of the GDPR, maximum fines can reach up to €20 million or 4% of a company's total global annual turnover from the preceding fiscal year, whichever amount is higher (Bloomberg Law, n.d.). Less severe violations (Art. 83(4) GDPR) carry fines of up to €10 million or 2% of global turnover (Intersoft Consulting, n.d.). These fines are explicitly intended to be "effective, proportionate and dissuasive" (Intersoft Consulting, n.d.). A crucial aspect of this enforcement framework is the broad definition of "undertaking," which allows an entire corporate group to be treated as one entity, with its total worldwide annual turnover used to calculate the fine for an infringement by one of its companies (Intersoft Consulting, n.d.). The proceeds from these substantial fines become national funds and are integrated into the respective national budgets, as illustrated below. Enforcement is primarily handled by national data protection authorities.

Fines

National Regulatory Body

(BfDI in Germany,

CNIL in France)

of the Respective Country

Budget (Revenue)

GDPR represents a strategic move by the EU to assert its values (fundamental rights) and economic interests (digital single market) in the global digital economy, using data protection as a tool for both. The EU's decision to replace a directive with a directly applicable regulation and to implement significantly higher fines signals a strong, unwavering commitment. This initiative extends beyond merely protecting citizens; it also aims to create a predictable and trustworthy environment for economic activity within the EU's digital single market. By setting a high standard and enforcing it globally, the EU effectively "exports" its regulatory framework, compelling international businesses to align with its values. The call for "European digital sovereignty" further underscores this geopolitical and economic dimension, positioning data protection as a cornerstone of the EU's digital strategy (Kavya, 2025).

2. Foundational Pillars of the GDPR: Principles and Rights

2.1 The Seven Core Principles of Data Processing: A Framework for Lawful and Ethical Data Handling

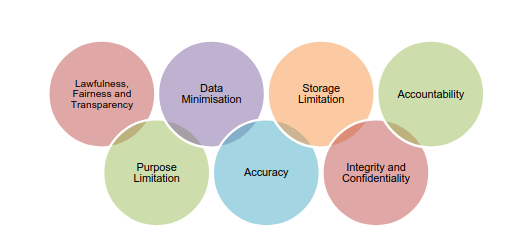

At the heart of the GDPR are seven core principles that collectively summarize its extensive requirements, guiding organizations toward overall compliance (Kosling, 2024). Adherence to these principles is fundamental for lawful, fair, and transparent data processing.

- Lawfulness, Fairness, and Transparency: This principle mandates that data processing must be legal, fair, and open (Anon., n.d.). To process data lawfully, organizations must meet at least one of GDPR's lawful bases for processing, such as obtaining explicit consent, fulfilling a contractual necessity, or pursuing a legitimate interest (Kosling, 2024). Fairness dictates that processing should not be unduly detrimental, unexpected, or misleading to data subjects. Transparency requires organizations to be clear, open, and honest with individuals about how their data will be used, typically communicated through comprehensive privacy notices (Kosling, 2024).

- Purpose Limitation: Personal data can only be collected for "specified, explicit and legitimate purposes" (Anon., n.d.). Once collected, data should not be further processed in a manner incompatible with those initial purposes. However, the GDPR allows for greater flexibility for further processing when data is used for archiving purposes in the public interest, scientific or historical research, or statistical purposes (Kosling, 2024).

- Data Minimisation: This principle dictates that organizations should collect and process only the "adequate, relevant and limited" data strictly necessary for the stated purpose (Anon., n.d.). The aim is to avoid excessive data collection, thereby reducing the potential impact in case of a breach and simplifying data accuracy and maintenance (Kosling, 2024).

- Accuracy: Personal data must be accurate and, where necessary, kept up to date (Anon., n.d.). Organizations are required to take "every reasonable step" to rectify or erase inaccurate or incomplete data promptly. It is also important to maintain records of any challenges to data accuracy (Kosling, 2024).

- Storage Limitation: Personal data should be retained "no longer than is necessary" for the purposes for which it was processed (Anon., n.d.). Organizations must establish clear data retention policies and schedules, periodically reviewing their data holdings and securely deleting data when it is no longer required (Kosling, 2024).

- Integrity and Confidentiality (Security): This principle requires that personal data be processed in a manner that ensures "appropriate security," protecting it from unauthorized or unlawful processing, accidental loss, destruction, or damage (Anon., n.d.). This necessitates the implementation of "appropriate technical or organisational measures," which can include encryption, access controls, and staff training (Kosling, 2024). Considering data availability—ensuring data is accessible when needed—is also recommended (Kosling, 2024).

- Accountability: Organizations must be able to "demonstrate compliance" with all the other principles (Anon., n.d.). This involves maintaining records of processing activities, conducting Data Protection Impact Assessments (DPIAs), implementing relevant policies and procedures, and potentially appointing a Data Protection Officer (DPO) (Kosling, 2024).

These principles collectively shift the burden of proof and responsibility for data protection from the individual to the organization, embedding privacy "by design and by default." Historically, individuals bore a significant burden in protecting their privacy. GDPR's "accountability" principle fundamentally shifts this, requiring organizations to proactively demonstrate their compliance. Principles like "data minimisation" and "purpose limitation" compel organizations to consider privacy at the initial stages of any data processing activity, rather than as an afterthought. This proactive integration of privacy into system design and business processes is encapsulated by the "privacy by design and by default" concept, making data protection an inherent feature of operations, which represents a significant advancement over previous reactive approaches (CDW, n.d.). The detailed nature of these principles provides a universal blueprint for ethical data handling, making GDPR a de facto global standard even for non-EU entities. The comprehensive and prescriptive nature of GDPR's principles offers a clear, actionable framework for any organization, regardless of its location, that handles personal data. As GDPR is recognized as "one of the world's strictest" and has "inspired privacy regulations throughout the world," many multinational companies find it more efficient and strategically advantageous to adopt these high standards globally. This effectively elevates GDPR's principles beyond a regional regulation to a benchmark for ethical data governance worldwide, demonstrating its necessity in shaping global best practices (Wenham, 2024).

Table 1: Key Principles of GDPR and Their Practical Implications

| Principle | Explanation | Practical Implications for Organizations |

|---|---|---|

| Lawfulness, Fairness, and Transparency | Data processing must be legal, fair, and open. Organizations must have a lawful basis for processing and be clear with data subjects about data use. | Use privacy notices to clearly communicate data usage. Ensure all processing aligns with legal bases and avoids misleading practices (Kosling, 2024). |

| Purpose Limitation | Personal data can only be collected for specified, explicit, and legitimate purposes, and not processed incompatibly with those purposes. | Clearly define and document specific data collection purposes. Assess if new purposes require fresh consent (Kosling, 2024). |

| Data Minimisation | Collect and process only the adequate, relevant, and limited data necessary for the stated purpose. | Regularly review data collected to ensure strict necessity. Implement processes to prevent over-collection, reducing breach impact (Kosling, 2024). |

| Accuracy | Personal data must be accurate and kept up to date. Inaccurate or incomplete data must be rectified or erased promptly. | Establish procedures for regular data review and updates. Provide mechanisms for data subjects to report inaccuracies. Keep records of challenges and corrections (Kosling, 2024). |

| Storage Limitation | Personal data should be retained only as long as necessary for the purposes for which it was processed. | Document standard retention periods for data types. Periodically review and securely delete data no longer required (Kosling, 2024). |

| Integrity and Confidentiality | Personal data must be processed securely, protected from unauthorized access, modification, destruction, or loss through appropriate technical and organizational measures. | Conduct risk assessments. Implement technical controls (e.g., encryption, firewalls) and organizational controls (e.g., staff training, policies) (Kosling, 2024). |

| Accountability | Organizations must be able to demonstrate compliance with all other principles. | Maintain records of processing activities, conduct DPIAs, implement policies/procedures, and consider appointing a DPO (Kosling, 2024). |

2.2 Empowering the Individual: Enhanced Data Subject Rights

GDPR significantly reinforces existing data protection rights and introduces new ones, collectively empowering data subjects and shifting control over personal data back to them (European Data Protection Supervisor, n.d.). These rights provide individuals with greater agency and transparency regarding how their personal information is handled:

Beyond these specific rights, GDPR also provides a "private right of action," allowing individuals to bring claims to protect their rights more swiftly than through regulatory bodies alone (Schroeder & Bravo, 2025). The introduction of specific, actionable data subject rights directly addresses the power imbalance between individuals and large data- processing entities, shifting control back to the individual. Prior to GDPR, individuals often lacked clear mechanisms to understand or control how their personal data was being used by organizations. The explicit articulation of rights such as the "right to be forgotten" and "data portability" provides concrete legal tools for individuals to assert agency over their digital footprint. Furthermore, the "private right of action" empowers individuals to directly challenge non-compliance, creating a direct legal incentive for organizations to respect these rights. This shift from a passive consumer to an empowered data subject represents a fundamental change driven by GDPR's necessity to rebalance power in the digital realm. These rights also foster greater transparency and trust between data subjects and organizations, which can translate into competitive advantages for compliant businesses. When individuals are aware of their rights and perceive that organizations are transparent and accountable in their data practices, their trust in those organizations increases. Evidence indicates that when businesses openly communicate about their data practices, customers are more likely to engage with them, as people care about their personal data being handled properly (Yacoob, 2025). This enhanced trust, built on the foundation of GDPR-mandated transparency and control, becomes a significant "competitive advantage," as consumers increasingly prefer and reward companies that prioritize data privacy (Yacoob, 2025).

2.3. Enforcement and Accountability: Deterrence and Compliance Mechanisms

GDPR enforcement is primarily a function of national data protection authorities (DPAs) within each EU member state. These independent public authorities are empowered to investigate breaches, conduct audits, and impose administrative fines and other corrective measures (Wenham, 2024).

The regulation introduced significantly higher sanctions than previous frameworks, specifically designed to be "effective, proportionate and dissuasive" (Intersoft Consulting, n.d.). For severe violations, categorized under Article 83(5) of the GDPR, fines can reach up to €20 million or 4% of a company's total global annual turnover from the preceding fiscal year, whichever is higher (Bloomberg Law, n.d.). Less severe violations, outlined in Article 83(4) GDPR, carry fines of up to €10 million or 2% of global turnover (Intersoft Consulting, n.d.). A crucial aspect of this framework is the broad definition of "undertaking," which means an entire corporate group can be treated as one entity, and its total worldwide annual turnover used to calculate the fine for an infringement by one of its companies (Intersoft Consulting, n.d.). The proceeds from these substantial fines become national funds and are integrated into the respective national budgets, as explicitly stated and illustrated below (Intersoft Consulting, n.d.).

Fines

National Regulatory Body

(BfDI in Germany,

CNIL in France)

of the Respective Country

Budget (Revenue)

The significantly higher fines and broader definition of "undertaking" under GDPR directly address the "limp-wristed" enforcement and low fines of the past, creating a powerful financial deterrent for non-compliance. Prior to GDPR, large data companies often faced low fines, sometimes less than what they might pay a single entry-level engineer in a year (Hoofnagle, et al., 2019). This minimal financial consequence meant that non-compliance was often a calculated business risk rather than a prohibitive one. The GDPR's maximum fines, coupled with the "undertaking" concept that can encompass an entire corporate group, fundamentally alters this calculus. The multi-billion Euro fines levied against tech giants demonstrate that penalties are now substantial enough to genuinely impact even the largest multinational corporations, thereby creating a powerful and necessary financial incentive for compliance.

In the seven years since GDPR came into force, over 2,632 violations have led to enforcement actions, totaling approximately €1.6 billion in fines (Schroeder & Bravo, 2025). The largest fines have predominantly been issued to U.S. Big Tech companies, such as Meta, Amazon, and TikTok, largely due to the immense volume of personal data they process (Schroeder & Bravo, 2025).

Notable examples of major fines include:

- Meta Platforms Ireland Ltd.: Received a record-breaking €1.2 billion fine in 2023 for violating GDPR international transfer guidelines, specifically for mishandling personal data transfers between Europe and the U.S. based on standard contractual clauses (de Chazal, 2025).

- Amazon Europe: Fined €746 million in 2021 for non-compliance with general data processing principles related to its use of customer data for targeted advertising (de Chazal, 2025).

- TikTok: Issued a €530 million fine in 2025 for transferring European users' personal data to servers in China without ensuring protections equivalent to those required under EU law (de Chazal, 2025).

- Meta Platforms, Inc. (Instagram): Fined €405 million in 2022 following an inquiry into its processing of personal data of child users (de Chazal, 2025).

Beyond monetary penalties, DPAs can impose other corrective measures, such as ordering an end to a violation, instructing adjustments to data processing practices, or imposing temporary or definitive bans on data processing (Intersoft Consulting, n.d.). GDPR has also led to a significant increase in data breach notifications, with over 121,000 reported in 2020 alone, indicating heightened awareness and reporting obligations (Kavya, 2025).

Despite these significant actions, some observations suggest ongoing challenges in consistent and timely enforcement across the EU. For instance, data indicates that as few as 1.3% of GDPR cases are resolved using fines, and some DPAs, such as Ireland's, have faced massive backlogs in case resolution (Schroeder & Bravo, 2025). This presents a nuanced picture: while the potential for severe penalties is high and has been demonstrated in high-profile cases, the actual consistent application of fines across all cases and member states might vary. This suggests that while GDPR has strong punitive power, the operational capacity and political will of all national DPAs to fully utilize its enforcement powers might differ, potentially leading to an uneven enforcement landscape and slower redress for data subjects. This points to an area for future improvement and continued monitoring of GDPR's practical effectiveness.

Table 2: Major GDPR Fines and Violations (Selected Cases)

| Company Name | Fine Amount (€) | Year | GDPR Breach Article(s) | Brief Description of Violation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Meta Platforms Ireland Ltd. | 1.2 billion | 2023 | Art. 46 (1) | Mishandling of personal data transfers between Europe and the U.S. without adequate protection (de Chazal, 2025). |

| Amazon Europe | 746 million | 2021 | Non-compliance with general data processing principles | Misuse of customer data for targeted advertising purposes (de Chazal, 2025). |

| TikTok | 530 million | 2025 | Art. 13 (1) f), Art. 46 (1) | Transfer of European users' personal data to China without equivalent protections (de Chazal, 2025). |

| Meta Platforms, Inc. (Instagram) | 405 million | 2022 | Art. 5 (1) a), c), Art. 6 (1), Art. 12 (1), Art. 24, Art. 25 (1), (2), Art. 35 | Processing of personal data of child users on Instagram (de Chazal, 2025). |

3. GDPR as a Global Standard: Extraterritorial Reach and International Influence

3.1. Defining the Global Scope: Who Must Comply?

One of the most defining and impactful features of the GDPR is its extraterritorial reach. This means that the regulation applies to any organization that processes the personal data of individuals residing in the European Union, irrespective of the company's physical location or where the processing takes place (Kavya, 2025).

Specifically, GDPR's jurisdiction extends to companies outside the EU if they engage in activities such as offering goods or services to, or monitoring the behavior of, EU data subjects (Bloomberg Law, n.d.). For instance, a U.S.-based web developer targeting businesses in the EU would be legally obligated to comply with GDPR (Bloomberg Law, n.d.). This broad scope means that even a Canadian citizen visiting Paris is protected by GDPR when looking up restaurants on Google, whereas a Spanish citizen visiting the U.S. would not be protected by GDPR when accessing a museum's website there (Schroeder & Bravo, 2025).

There are limited exceptions to this expansive scope. The regulation does not apply to the "processing of personal data for purely personal or household activity," such as an individual collecting emails for a personal book club, where encryption would not be required as it would be for commercial data collection (Bloomberg Law, n.d.). Additionally, organizations with fewer than 250 employees may be exempt from certain GDPR requirements if their processing of user data does not pose a risk to the data subject (Bloomberg Law, n.d.). Data Protection Authorities (DPAs) in each EU member state are responsible for enforcing this compliance, regardless of the company's global presence (Wenham, 2024).

GDPR's extraterritoriality fundamentally reshaped global business practices, forcing a universal baseline for data protection that transcends national borders. The fact that a business in the U.S., Australia, or any other non-EU country must comply with GDPR if it processes the personal data of EU residents transforms GDPR from a regional law into a de facto global market entry requirement (Wenham, 2024). This has led many multinational companies to adopt GDPR-like standards globally, rather than maintaining complex, separate data processing systems for different jurisdictions. This operational simplification, driven by the need to access the EU market, effectively elevates GDPR's principles to a universal standard, demonstrating its necessity in harmonizing data protection on a global scale. The extraterritorial scope directly addresses the "loophole" of companies operating outside the EU but impacting EU citizens, ensuring consistent data protection regardless of where the data controller is established. The Data Protection Directive's limitation to companies operating within the EU created a significant gap, allowing foreign entities to process EU citizens' data without direct accountability under EU law (Dessaints, n.d.). GDPR's explicit and broad extraterritoriality was a direct response to this deficiency. By asserting jurisdiction over any entity that offers goods or services to, or monitors the behavior of, EU residents, GDPR ensures that the fundamental rights of EU data subjects are protected consistently, regardless of the physical location of the data controller. This closing of the "loophole" was a necessary step to maintain the integrity of EU data protection in a globally interconnected digital landscape (Dessaints, n.d.).

Impact of Reputational Damage and Loss of Customer Trust:

Beyond financial penalties, GDPR non-compliance can severely impact a business's reputation, leading to a significant loss of customer trust and confidence (Nambiar, 2025); (George, 2025); (Neumetric, n.d.); (Sadoian, 2025). Publicized fines and enforcement actions damage brand credibility and deter potential customers and partners who prioritize data privacy (George, 2025). Surveys indicate a strong consumer concern for data privacy: 70% of those surveyed trust the DPC to uphold their rights (Data Protection Commission, 2025), and 2 out of 3 people would trust an organization "a lot less" if it misused personal data (Data Protection Commission, 2025). Critically, 70% of consumers would stop shopping with a brand after a security incident (Vercara, 2024); (Doerer, 2025). While consumer apathy towards breaches increased slightly in 2024 (58% impact on trust, down from 62% in 2023), the fundamental impact on a business's bottom line remains severe, as a significant portion of customers are willing to disengage from brands that fail to protect their data (Vercara, 2024); (Doerer, 2025).

Operational Disruptions and Legal Costs:

Investigations and enforcement actions by regulatory authorities can significantly disrupt business operations, requiring substantial resources to address compliance gaps and implement necessary changes (Nambiar, 2025); (George, 2025); (Neumetric, n.d.); (Sadoian, 2025). This can lead to delays, financial strain, and diverted focus from core business activities (George, 2025). Non-compliance also exposes businesses to potential legal challenges, including class-action lawsuits from affected data subjects seeking compensation for material or non-material damages (Nambiar, 2025); (George, 2025); (Neumetric, n.d.). Defending against these actions incurs substantial legal fees, further draining organizational resources (Nambiar, 2025); (Neumetric, n.d.).

3.2 Shaping International Data Protection Frameworks

- GDPR has inspired privacy regulations worldwide;

- Influence extends to public, corporate and institutional expectation for data governance;

- Schrems II decision (2020) by the Court of Justice of the EU invalidated the EU-U.S. Privacy Shield, citing inadequate protection due to U.S. surveillance laws;

- Cloud services, especially those hosted on U.S. servers, face added complexity;

- EU regulators may scrutinize UK adequacy status if UK–U.S. agreements lack sufficient safeguards.

The GDPR is widely recognized as a "global benchmark" and "gold standard" for privacy, having "inspired privacy regulations throughout the world" (Wenham, 2024). Its influence is evident in the adoption of similar privacy laws in various jurisdictions globally. For instance, several U.S. states have implemented their own privacy laws, with California's Consumer Privacy Act (CCPA) being the most prominent example. While these U.S. state laws share similarities with GDPR, they may not be as comprehensive or uniform (Wenham, 2024). Businesses operating in the U.S. are frequently advised to adopt GDPR principles as a best practice, particularly if they handle international data (Wenham, 2024). This demonstrates that GDPR has catalyzed a global shift towards more robust, rights-based data protection frameworks, creating a "GDPR effect" where other jurisdictions emulate its principles. The consistent description of GDPR as a "global benchmark" and its direct influence on the development of laws like California's CCPA demonstrates a clear, observable trend in international data protection. This "GDPR effect" extends beyond mere legal compliance, as it sets a new, higher expectation for how personal data should be handled worldwide. Jurisdictions are increasingly recognizing the societal and economic benefits of strong data protection, leading them to adopt similar principles, thereby reinforcing GDPR's necessity as a model for global regulatory convergence.

A critical aspect of GDPR's global influence lies in its stringent regulation of international data transfers. GDPR specifies acceptable methods for transferring personal data outside the EU, such as Standard Contractual Clauses (SCCs), Binding Corporate Rules (BCRs), or an "adequacy decision," where the European Commission determines that a non-EU country's privacy laws provide comparable protection (Schroeder & Bravo, 2025).

The landmark "Schrems II" decision by the Court of Justice of the European Union in July 2020 profoundly impacted trans-Atlantic data flows. This ruling invalidated the EU-U.S. Privacy Shield Framework, which over 5,000 U.S. companies had relied upon for data transfers (Kavya, 2025). The Court determined that Privacy Shield did not confer an "adequate level of data protection" due to concerns about U.S. surveillance programs lacking necessary and proportional safeguards (Schroeder & Bravo, 2025). This decision mandated that companies conduct individual assessments of each data transfer to non- EU countries to ensure equivalent data protection standards (Kavya, 2025). This has added significant complexity for cloud services, given that a substantial portion of Western data is stored on U.S.-owned servers (Kavya, 2025). Concerns have also been raised about the UK's data-sharing agreements with the US post-Brexit in light of this decision (Kavya, 2025). The Schrems II decision highlights the EU's unwavering commitment to its fundamental data protection rights, even at the cost of disrupting major international data transfer mechanisms, underscoring the necessity of genuine "equivalent protection." The invalidation of the EU-U.S. Privacy Shield was not a minor regulatory adjustment but a significant disruption to trans-Atlantic data flows. This drastic measure, rooted in the finding that U.S. surveillance practices did not provide an "adequate level of data protection," unequivocally signals that the EU prioritizes the substance of fundamental data protection rights over procedural convenience or economic considerations. It compels global entities to genuinely align their data handling practices with EU standards, emphasizing that merely having a framework is insufficient; the framework must deliver equivalent protection. This demonstrates the critical necessity of GDPR in ensuring that data subject rights are not merely theoretical but practically enforceable across borders.

4. Sectoral Deep Dive: Necessity and Impact Across Key Industries

4.1. The Financial Sector: Safeguarding Sensitive Data and Ensuring Trust

The financial and insurance sectors, already operating under a dense web of regulations, face additional layers of complexity due to the GDPR (CDW, n.d.). These industries routinely process vast amounts of personal data, much of which is highly sensitive, particularly when complying with Know Your Customer (KYC) and Anti-Money Laundering (AML) requirements (DPO Centre, n.d.). This sensitive data can encompass credit card numbers, bank statements, and even criminal records.

4.1.1. Unique Data Processing Challenges and Regulatory Overlap

- Strict legislation for use of data for profiling and automated decision-making under EU and UK GDPR;

- Managing data across multiple legacy systems poses a challenge for data minimization;

- Robust network and server security paramount for integrity and confidentiality;

- GDPR compliance needs to be aligned with other complementary regulations;

- Critical for protecting wider financial ecosystem.

Financial institutions must ensure that collected data is used strictly for its intended purpose, shared only in a controlled manner, and retained and disposed of appropriately and in a timely fashion (DPO Centre, n.d.). The use of data for profiling and automated decision-making, which is common in finance for activities such as credit scoring, fraud detection, or personalized financial advice, is subject to strict legislation under both EU and UK GDPR (DPO Centre, n.d.). A significant operational challenge arises from managing personal data across multiple and often legacy systems, which can lead to duplicated data and complicate efforts toward data minimization (DPO Centre, n.d.). Maintaining robust network and server security, implementing data encryption, and strong cybersecurity measures are paramount to protect the integrity and confidentiality of financial data (DPO Centre, n.d.). Furthermore, GDPR compliance is complicated by the need to align its requirements with a host of other complementary regulations, including Financial Conduct Authority (FCA) regulations, PCI Credit Card regulations, banking regulations, and Anti-Money Laundering laws (DPO Centre, n.d.).

GDPR's necessity in finance stems from the sector's unique position as a custodian of highly sensitive personal and financial data, where breaches have catastrophic trust and systemic implications. Financial institutions handle not just personal data, but "sensitive data" like credit card numbers and bank statements. The sheer volume and sensitivity of this data, coupled with existing stringent regulations, mean that a data breach in this sector carries profound risks beyond individual privacy, potentially destabilizing financial markets and eroding public trust in the entire system. GDPR's strict requirements for purpose limitation, data minimization, security, and accountability are therefore not merely about protecting individual rights but are critical for maintaining the fundamental integrity, stability, and trustworthiness of the financial ecosystem itself (DPO Centre, n.d.).

4.1.2. Compliance Imperatives and Strategic Advantages

- Must operate with transparency and accountability;

- DPO is mandatory due to large-scale processing of personal or special category data or the extensive use;

- Privacy must be an inherent consideration;

- Requires re-architecting data flows and systems.

Financial organizations must operate with transparency and accountability in their personal data processing, allowing data subjects to access, correct, and delete their stored data (unless legitimate reasons for retention exist) (DPO Centre, n.d.). Appointing a Data Protection Officer (DPO) is often mandatory for financial entities due to their large-scale processing of personal or special category data, or their extensive use of data for profiling and automated decision-making (DPO Centre, n.d.). The GDPR mandates incorporating "data protection by design and by default," meaning that privacy must be an inherent consideration when designing any business process, with a default assumption of privacy built into systems and operations (CDW, n.d.). The "by design and by default" principle forces financial institutions to fundamentally rethink their data infrastructure, moving beyond reactive security measures to proactive privacy integration. GDPR's mandate for "privacy by design and by default" means that simply adding security patches to existing legacy systems is insufficient. Instead, data protection must be an inherent consideration from the very inception of any new business process or system. This necessitates significant investment in re-architecting data flows and systems, pushing the industry towards a more proactive and integrated approach to privacy, which, while potentially costly, is necessary to mitigate the high risks associated with financial data (CDW, n.d.).

Beyond merely avoiding substantial fines, GDPR compliance positions financial institutions as forward-thinking and responsible entities, significantly enhancing customer trust and reputation (Anon., 2024). It also streamlines data management, improves data quality, and can lead to notable cost savings by preventing costly data breaches and automating compliance processes (Anon., 2024).

4.2. The Hospitality Sector: Managing Guest Data and Reputational Resilience

The hospitality sector, encompassing hotels and related services, is uniquely positioned as a business that frequently handles a vast amount of personal data. This includes sensitive guest information such as names, payment details, passport information, dietary preferences, and even "special category data" like health information provided for specific accommodations (Bryne, n.d.).

4.2.1. High Volume of Personal Data and Third-Party Risks

- Requires providing clear privacy notices and obtaining informed consent for extensive use of data or collection of sensitive data;

- Challenge arises from practice of collaboration from third-party service providers;

- Hotels are responsible for ensuring third party compliance;

- Due diligence, DPAs and continuous monitoring is required to ensure compliance across the data supply chain.

Hotels must rigorously adhere to GDPR's core principles, including lawfulness, fairness, transparency, purpose limitation, data minimization, accuracy, storage limitation, and integrity/confidentiality (Bryne, n.d.). This involves providing clear privacy notices to guests and obtaining valid, specific, and informed consent for activities like marketing communications or the collection of sensitive data (Bryne, n.d.).

A significant challenge in this sector arises from the common practice of collaborating with numerous third-party providers, such as booking platforms, payment processors, and housekeeping services. Under GDPR, hotels, as data controllers, remain ultimately responsible for ensuring that these third parties also comply with data protection requirements. This necessitates the establishment of robust Data Processing Agreements (DPAs) that clearly outline the responsibilities of each party and safeguard the data being shared (Bryne, n.d.). The prevalence of third-party data processors in hospitality creates a distributed risk landscape, making the controller's accountability for all data processing activities a critical and complex challenge. Hotels frequently outsource core functions like booking and payment processing to third-party providers. While this optimizes operations, GDPR holds the hotel (as the data controller) ultimately responsible for ensuring that these third parties also comply with data protection requirements. This means hotels must engage in rigorous due diligence, implement robust Data Processing Agreements, and continuously monitor the compliance of their entire data supply chain. The Marriott breach, which originated from a vulnerability in an acquired entity, exemplifies how vulnerabilities within this distributed data processing ecosystem can lead to massive penalties for the primary data controller, highlighting the complex systemic risk management aspect that GDPR necessitates (Bryne, n.d.).

Data breaches in the hospitality sector can lead to severe financial penalties and significant reputational damage (Bryne, n.d.). The Marriott International case serves as a prominent example, where the company faced a $52 million fine from The Federal Trade Commission (FTC) following a major data breach that compromised millions of guest records (Bryne, n.d.). Such incidents can profoundly erode customer trust, lead to potential legal action, and result in substantial revenue losses, with some reports estimating up to a 30% loss in revenue following a breach (Andersen, G.; MoldStud Research Team;, 2025). Common compliance failures observed in this sector include inadequate staff training, insufficient security measures, and poor data consent protocols (Andersen, G.; MoldStud Research Team;, 2025). The cost of rectifying breaches can be substantial, often exceeding the penalty amount itself (Andersen, G.; MoldStud Research Team;, 2025). Hotels must also implement strict data retention policies for sensitive data, ensuring it is securely deleted when no longer necessary (Bryne, n.d.).

4.2.2. Building Customer Loyalty Through Privacy

- An industry heavily reliant on trust;

- Failure to protect personal data entrusted by guests severely damages trust;

- GDPR compliance as a differentiator;

- 94% customers favour companies prioritizing data privacy

GDPR compliance is essential not just to avoid fines but as a strategic advantage for hotels (Yacoob, 2025). It positions hotels as responsible and forward-thinking, thereby enhancing customer trust and loyalty (Yacoob, 2025). In an industry heavily reliant on word-of-mouth and online reviews, maintaining a strong reputation is crucial (Bryne, n.d.). Guests entrust hotels with their personal data, and a failure to protect it can severely damage this trust (Bryne, n.d.). Evidence suggests that a high percentage of consumers (94%) favor companies that prioritize data privacy, making GDPR compliance a significant competitive differentiator (Yacoob, 2025). It also contributes to improved operational efficiency and ensures readiness for evolving legal requirements (Bryne, n.d.). Conducting Data Protection Impact Assessments (DPIAs) and providing comprehensive staff training are critical compliance measures to safeguard guest data (Bryne, n.d.). In the hospitality sector, GDPR compliance directly translates into reputational resilience and competitive advantage, demonstrating that privacy is no longer just a legal burden but a market differentiator. The hospitality industry's business model is highly dependent on customer trust and positive public perception, which is significantly influenced by online reviews and word-of-mouth. Data breaches not only incur substantial fines but also lead to severe "tarnished reputations and loss of customer trust," potentially resulting in significant revenue losses. Conversely, actively demonstrating GDPR compliance, by being transparent and securing guest data, builds "customer trust, customer loyalty and increased brand reputation." The statistic that "94% of consumers favour companies that prioritise data privacy" clearly illustrates that privacy is a consumer expectation that can be leveraged for market differentiation, making GDPR compliance a strategic imperative beyond mere legal obligation (Yacoob, 2025).

4.3. Emerging Technologies: Navigating the Frontier of Data Privacy

The rapid evolution of emerging technologies presents novel and complex challenges for data privacy, making GDPR's principles and requirements particularly critical. Technologies such as Artificial Intelligence (AI), the Internet of Things (IoT), and Blockchain fundamentally alter how data is collected, processed, and stored, necessitating careful consideration of GDPR compliance.

4.3.1. Artificial Intelligence (AI): Balancing Innovation and Rights

Artificial Intelligence (AI) systems, especially those involving machine learning and large language models (LLMs), often require processing vast volumes of data. If these systems use data belonging to EU citizens or are intended for deployment in the EU, they must strictly adhere to GDPR's requirements (Anon., n.d.).

GDPR's impact on AI development is multi-faceted:

- Justifiable Grounds for Data Management: GDPR mandates explicit consent for the use of personal data by AI models. AI developers must ensure consent is willingly provided, specific, informed, and unequivocal. While "legitimate interest" can sometimes serve as a lawful basis, it requires a careful balance to ensure data subject rights are not compromised (Anon., n.d.).

- Data Minimisation and Purpose Restriction: AI mechanisms must comply with the principle that only the minimal required data should be used for any specific purpose, preventing the collection or manipulation of unnecessary data. Data collected for one purpose should not be repurposed without additional consent (Anon., n.d.).

- Anonymisation and Pseudonymisation: AI systems are expected to employ anonymisation and pseudonymisation methods. Anonymisation permanently prevents identification, while pseudonymisation replaces private identifiers with fake ones, safeguarding privacy while allowing AI systems to derive insights from large datasets (Anon., n.d.).

- Protection and Accountability: AI systems must integrate robust security practices to prevent data infringements and unauthorized access. Both AI developers and users are held accountable, requiring records of data manipulation, impact assessments, and the incorporation of data protection by design and by default (Anon., n.d.).

- Individual Rights: GDPR grants specific rights concerning data use in AI models:

- Access and portability: Individuals can access their data and obtain it for reuse, requiring AI systems to facilitate data recovery and transfer (Anon., n.d.).

- Right to explanation: Individuals are entitled to understand the reasoning behind decisions made through automated processing, necessitating transparent and understandable AI decision-making methodologies (Anon., n.d.).

- Right to be forgotten: Individuals can demand the erasure of their personal data, requiring AI systems to have mechanisms for complete data erasure upon request (Anon., n.d.).

Data Protection Impact Assessments (DPIAs) are a requirement for AI systems handling high-risk processes, assisting in detecting and mitigating data processing risks (Anon., n.d.). The underlying theme is that GDPR forces AI development to embed ethical considerations and individual rights from inception, challenging the traditional "move fast and break things" ethos with a "privacy by design" imperative. The explicit requirements for consent, data minimization, and accountability compel AI developers to consider privacy at every stage of the AI lifecycle, from data acquisition to model deployment. This proactive approach ensures that ethical considerations are not an afterthought but an integral part of AI system design, fostering more trustworthy and human-centric AI. The "right to explanation" and "right not to be subject to automated decision-making" directly challenge the opacity of complex AI models, necessitating greater transparency and human oversight in algorithmic decision-making. These rights demand that AI systems provide understandable methodologies for decisions that significantly affect individuals. This pushes AI developers beyond mere technical functionality, requiring them to design systems that are not only effective but also interpretable and justifiable to the data subjects they impact, thereby promoting fairness and preventing potential discrimination or bias inherent in black-box algorithms (Anon., n.d.).

4.3.2. Internet of Things (IoT): Consent, Control, and Security at Scale

The Internet of Things (IoT), defined as a global network infrastructure linking physical and virtual objects through data capture and communication, presents several unique challenges for GDPR compliance (Team LEXR, 2024). IoT devices often process personal data, including IP addresses, phone numbers, and location data (Legal IT Group, 2025).

Key challenges for IoT data processing under GDPR include:

- Struggling Sensitive Data & Consent: The core of IoT functionality relies on machine-to-machine (M2M) communication, often without human intermediation, making obtaining explicit consent difficult. Many IoT devices lack an interface to display privacy information or consent forms. Automated decision-making, a key feature of IoT, is prohibited without consent if it significantly impacts an individual, unless necessary for contract performance (Team LEXR, 2024).

- Keeping Up with Data Subject Rights: IoT developers face obstacles in designing devices that can comply with rights like the "right to be forgotten," partly due to interoperability issues. The complexity of data processing and analytics in the cloud, involving multiple parties, necessitates carefully drafted data processing agreements to ensure assistance in fulfilling data subject requests. Communication between IoT devices often occurs without individual awareness, making data flow control nearly impossible for the individual (Team LEXR, 2024).

To minimize GDPR exposure, "privacy by design" principles are crucial for IoT:

- Achieve Consent: Embed consent mechanisms directly into devices where technically feasible, or broadcast data protection information to nearby mobile devices via dedicated apps (Team LEXR, 2024).

- Put Users in Control: Provide granular choice over data capture (category, time, frequency), inform users when smart devices are active, and offer "do not collect personal data" options. Limit data distribution by transforming raw data into aggregated data and deleting raw data immediately. Enforce local control by facilitating local storage and processing without requiring data transmission, and provide tools for users to locally read, edit, and modify data (Team LEXR, 2024).

- Implement Adequate Security Measures: Reduce the attack surface, regularly test for vulnerabilities, dispatch security updates, encrypt personal data (at rest and in transit), and ensure M2M communications over secure channels (Team LEXR, 2024).

- Minimize Data Collection: Limit data collection to what is truly needed, ensuring it conforms with GDPR and does not create compliance obstacles (Team LEXR, 2024).

IoT projects typically need to conduct a Data Protection Impact Assessment (DPIA), especially given their use of new technologies and potential for high risk to data subjects' rights (Legal IT Group, 2025). The underlying theme is that IoT's pervasive data collection challenges the very notion of informed consent and individual control, making GDPR's "privacy by design" principle a critical, yet difficult, mandate for device manufacturers. The continuous, often invisible, data flow from IoT devices makes it challenging for individuals to understand what data is collected, how it is used, and to exercise their rights. This necessitates a fundamental shift in design philosophy, requiring manufacturers to embed privacy safeguards and user control mechanisms directly into the devices and their ecosystems from the outset, rather than attempting to layer them on later. The inherent lack of user interfaces and continuous data flow in many IoT devices necessitates a re- evaluation of how consent is obtained and how data subject rights (like erasure) are practically implemented, pushing for innovative "privacy-enhancing technologies." Traditional consent models, reliant on explicit user interaction, are often impractical for IoT devices. This forces developers to explore alternative mechanisms for consent and to design systems that can honor rights such as the right to erasure, even when data is distributed and continuously generated. This pushes for the development of new technological solutions that can reconcile the functionality of IoT with the fundamental rights enshrined in GDPR (Team LEXR, 2024).

4.3.3. Blockchain Technology: Immutability vs. Erasure

Blockchain technology, known for its decentralized and immutable nature, offers a revolutionary approach to data storage and verification (Grathwohi, 2025). However, this core characteristic directly clashes with stringent data protection laws, particularly the GDPR's "right to be forgotten" (Grathwohi, 2025).

The fundamental conflict arises because blockchain's design ensures that once data is added to the digital ledger, it cannot be changed or deleted without extreme difficulty (Grathwohi, 2025). This immutability is a direct result of cryptographic hashing and decentralization: each block is cryptographically linked to the previous one, and altering one block would disrupt the entire chain. Furthermore, the decentralized structure means no single entity controls the network, requiring widespread consensus to alter data, which is practically impossible in large networks (Grathwohi, 2025). The GDPR's "right to be forgotten" (Article 17) allows individuals to request the deletion of their personal data when its retention is no longer justified (Grathwohi, 2025). This creates a fundamental clash: if personal data is stored on a blockchain, there is no straightforward mechanism to remove or delete it once committed to the chain, unlike traditional centralized systems (Grathwohi, 2025). The fundamental design principle of blockchain (immutability) directly conflicts with a core GDPR right (right to erasure), creating a significant legal and technical dilemma for data governance. Blockchain's core value proposition is the creation of an unchangeable, verifiable record. This inherent immutability, while beneficial for trust and security in certain applications, directly contradicts the data subject's right to have their personal data deleted. This forces a re-evaluation of how personal data can be managed within blockchain systems, highlighting a deep tension between technological design and legal mandates.

Another layer of complexity is defining what constitutes "personal data" on the blockchain. While blockchain often uses pseudonymized or encrypted data, where users interact through cryptographic keys, GDPR broadly defines personal data as any information that can be linked back to an identifiable individual. This means data linked to a cryptographic key could still be considered personal data under GDPR if the key can be associated with a specific individual through external information (Grathwohi, 2025).

Despite this conflict, several technical solutions have been proposed to bring blockchain systems closer to GDPR compliance, though each has limitations:

- Off-Chain Storage: Personal data is stored outside the blockchain, with only a reference (e.g., a cryptographic hash) recorded on-chain. If an erasure request is made, the personal data is deleted from the off-chain storage, rendering the on-chain reference meaningless. However, the hash still exists on-chain, and this approach reintroduces centralized data management risks (Grathwohi, 2025).

- Encryption Key Destruction: Personal data is encrypted before being recorded on the blockchain. Upon a deletion request, the encryption key is destroyed, making the data inaccessible. While the data remains on-chain, its inaccessibility aims to satisfy GDPR's requirement to prevent further processing. However, the encrypted data technically remains on the blockchain, and future technological advancements could potentially break the encryption (Grathwohi, 2025).

- Permissioned Blockchains: These are managed by a smaller group of trusted entities with greater control over data. Governance rules can be implemented to allow for deletion or masking of personal data. However, they reintroduce elements of centralization, undermining some benefits of decentralized systems (Grathwohi, 2025).

The European Data Protection Board (EDPB) is unambiguous on this point: storing personal data directly on-chain is problematic, and directly identifiable data should be avoided entirely. Any use of blockchain must document the rationale for choosing it over other technologies, demonstrating its necessity and proportionality, especially when personal data is involved (Olejnik, 2025). Data Protection Impact Assessments (DPIAs) are strongly suggested before blockchain deployment, as its use may qualify as high-risk processing due to its complexity, scale, and potential for long-term impact on data subjects (Olejnik, 2025). The tension between blockchain and GDPR highlights a broader challenge for legal frameworks: adapting to technologies whose core functionalities inherently challenge established legal rights, pushing for innovative legal interpretations or technological workarounds. This conflict underscores the dynamic nature of data protection law, which must continuously evolve to address the implications of emerging technologies. It forces a dialogue between technologists and legal experts to find solutions that uphold fundamental rights while allowing for technological innovation.

Conclusion

The General Data Protection Regulation stands as a testament to the European Union's unwavering commitment to individual privacy and data protection in an increasingly digitalized world. Its necessity is unequivocally demonstrated by the historical evolution of privacy concepts, the glaring inadequacies of its predecessor, the 1995 Data Protection Directive, and the imperative to establish a unified and robust legal framework for the digital single market.

GDPR's foundational pillars, comprising its seven core principles and enhanced data subject rights, fundamentally shift the paradigm of data governance. They place the burden of accountability squarely on organizations, demanding proactive "privacy by design and by default" and empowering individuals with unprecedented control over their personal data. The regulation's stringent enforcement mechanisms, characterized by substantial fines and the broad definition of "undertaking," serve as powerful deterrents, compelling global entities to prioritize compliance. While challenges in consistent enforcement persist, the high-profile penalties levied against major tech companies underscore the seriousness with which GDPR is applied.

Furthermore, GDPR's extraterritorial reach has solidified its status as a global benchmark, influencing data protection laws and practices far beyond EU borders. The "GDPR effect" is evident in the development of similar regulations worldwide, and landmark decisions like "Schrems II" highlight the EU's unyielding demand for genuinely equivalent data protection standards in international transfers.

The analysis across the Finance, Hospitality, and Emerging Technologies sectors reveals GDPR's profound and transformative impact. In finance, it addresses the critical need to safeguard highly sensitive data, forcing a fundamental rethinking of data infrastructure to ensure trust and systemic stability. For the hospitality industry, GDPR compliance is directly linked to reputational resilience and competitive advantage, emphasizing that privacy is a market differentiator in a sector built on customer trust. In the realm of emerging technologies, GDPR navigates the complex frontiers of AI, IoT, and Blockchain, challenging inherent design principles and pushing for ethical innovation that respects individual rights. It compels AI development to embed ethical considerations from inception, forces IoT manufacturers to re-evaluate consent and control in pervasive data environments, and creates a significant legal and technical dilemma for blockchain's immutability versus the right to erasure.

In sum, GDPR is not merely a set of rules; it is an indispensable framework that underpins trust, drives responsible innovation, and ensures the fundamental rights of individuals in the digital age. Its continued evolution and global influence will undoubtedly shape the future of data governance, underscoring its enduring necessity.

References

- University of Michigan. (n.d.). History of Privacy Timeline. From Safe Computing: https://safecomputing.umich.edu/protect-privacy/history-of-privacy-timeline

- Hoofnagle, C. J., van der Sloot, B., & Borgesius, F. Z. (2019). The European Union general data protection regulation: what it is and what it means. Information & Communications Technology Law, XXVIII(1), 65-98.

- Kavya. (2025). The GDPR Impact: Three Years On. From CookieYes Blog: https://www.cookieyes.com/blog/3-years-of-gdpr-impact/

- Wenham, P. (2024). Understanding the global standard for data protection. From AssuranceLab CPA: https://www.assurancelab.cpa/resources/understanding-the-global-standard-for-data-protection

- Bloomberg Law. (n.d.). The EU’s General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR). From Bloomberg Law: https://pro.bloomberglaw.com/insights/privacy/the-eus-general-data-protection-regulation-gdpr/

- Schroeder, C., & Bravo, M. V. (2025). The Seven Year Itch: On the GDPR’s Anniversary, A Look At Its History, Legacy, and Uncertain Future. From EPIC: https://epic.org/the-seven-year-itch-on-the-gdprs-anniversary-a-look-at-its-history-legacy-and-uncertain-future/

- Court of Justice of the European Union. (2024). Protection of personal data. s.l.: Research and Documentation Directorate.

- Dessaints, A. (n.d.). Data Protection Directive vs. GDPR: Key Differences and Impacts. From DPO Consulting Blog: https://www.dpo-consulting.com/blog/data-protection-directive-vs-gdpr

- Klekovic, I. (n.d.). EU GDPR vs. European data protection directive. From Advisera: https://advisera.com/articles/eu-gdpr-vs-european-data-protection-directive/

- Mondschein, C. F., & Monda, C. (2018). The EU’s General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) in a Research Context. In P. Kubben, M. Dumontier, & A. Dekker (Eds.), Fundamentals of Clinical Data Science [Internet]. s.l.: Springer.

- Yale University. (n.d.). European Union General Data Protection Regulation. From Yale Research Support: https://your.yale.edu/research-support/human-research/news-events/european-union-general-data-protection-regulation

- Anon. (n.d.). Data Protection Principles: Core Principles of the GDPR, Examples and Best Practices. From Cloudian: https://cloudian.com/guides/data-protection/data-protection-principles-7-core-principles-of-the-gdpr/

- Anon. (2024). Benefits of GDPR Compliance for Businesses in 2024. From Atlan: https://atlan.com/benefits-of-gdpr-compliance/

- Intersoft Consulting. (n.d.). GDPR Fines / Penalties. From GDPR Info: https://gdpr-info.eu/issues/fines-penalties/

- Kosling, K. (2024). GDPR: Understanding the 6 Data Protection Principles. From IT Governance Blog: https://www.itgovernance.eu/blog/en/the-gdpr-understanding-the-6-data-protection-principles

- CDW. (n.d.). Finance and GDPR: What You Need to Know. s.l.: s.n.

- European Data Protection Supervisor. (n.d.). The History of the General Data Protection Regulation. From EDPS: https://www.edps.europa.eu/data-protection/data-protection/legislation/history-general-data-protection-regulation_en

- Yacoob, S. Y. (2025). 7 Key Benefits of GDPR Compliance for Your Business in 2025. From CookieYes Blog: https://www.cookieyes.com/blog/benefits-of-gdpr-compliance/

- de Chazal, E. (2025). 20 Biggest GDPR Fines of All Time. From Skillcast: https://www.skillcast.com/blog/20-biggest-gdpr-fines

- Grathwohi, B. (2025). Balancing Privacy & Performance. From DDA Review: https://dda.ndus.edu/ddreview/balancing-privacy-performance/

- DPO Centre. (n.d.). Data Protection for Finance & Insurance. From DPO Centre: https://www.dpocentre.com/sector/finance-insurance/

- Bryne, P. (n.d.). How does GDPR apply to hotels?. From PropelFWD: https://propelfwd.com/how-does-gdpr-apply-to-hotels/

- Andersen, G.; MoldStud Research Team. (2025). Exploring Real-Life GDPR Compliance Failures in the Hospitality Industry with Valuable Lessons and Important Insights. From MoldStud: https://moldstud.com/articles/p-exploring-real-life-gdpr-compliance-failures-in-the-hospitality-industry-with-valuable-lessons-and-important-insights

- Anon. (n.d.). The Intersection of GDPR and AI and 6 Compliance Best Practices. From Exabeam: https://www.exabeam.com/explainers/gdpr-compliance/the-intersection-of-gdpr-and-ai-and-6-compliance-best-practices/

- Dentons. (2025). AI and GDPR Monthly Update Special Edition AI Implementation. From Dentons: https://www.dentons.com/en/insights/articles/2025/january/28/ai-and-gdpr-monthly-update-special-edition-ai-implementation

- Team LEXR. (2024). The Internet of Things in the GDPR era. From LEXR: https://www.lexr.com/en-ch/blog/iot-and-gdpr/

- Legal IT Group. (2025). GDPR and Internet of Things (IoT). From Legal IT Group: https://legalitgroup.com/en/gdpr-and-internet-of-things-iot/

- Olejnik, L. (2025). Blockchain and data protection (GDPR). From Lukasz Olejnik Blog: https://blog.lukaszolejnik.com/blockchain-and-data-protection-gdpr/

- European Parliament and the Counil of the European Union, 1995. Directive 95/46/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 24 October 1995 on the protection of individuals with regard to the processing of personal data and on the free movement of such data. Official Journal of the European Communities, L(281), pp. 31-50.